Marking the Dispossessed compiles hundreds of isolated reader’s marks found in a collection of used copies of Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1974 anarchist science fiction novel, The Dispossessed. Sometimes subtitled “An Ambiguous Utopia,” The Dispossessed is the story of a physicist, Shevek, who travels from his planet of anarchists, Anarres, to a sister planet, Urras. Le Guin describes Shevek’s confrontation with things he hasn’t experienced before, like class difference, gender hierarchy and personal property, as well as his perplexed encounters with everyday signs of excess, like the complicated layers of packaging around a box of chocolates. The book is organized with chapters that alternate between Shevek’s life on Anarres and Urras.

The project of compiling readers’ marks began after I first read The Dispossessed, around 2009. I was so moved by its contents and the possibility of a different social order that I didn’t want to leave it. This is something that often happens with good books — I am completely sucked in while reading but as soon as I’m done I immediately start forgetting why I liked it so much. This project is, in a way, an exercise in trying to spend more time with The Dispossessed.

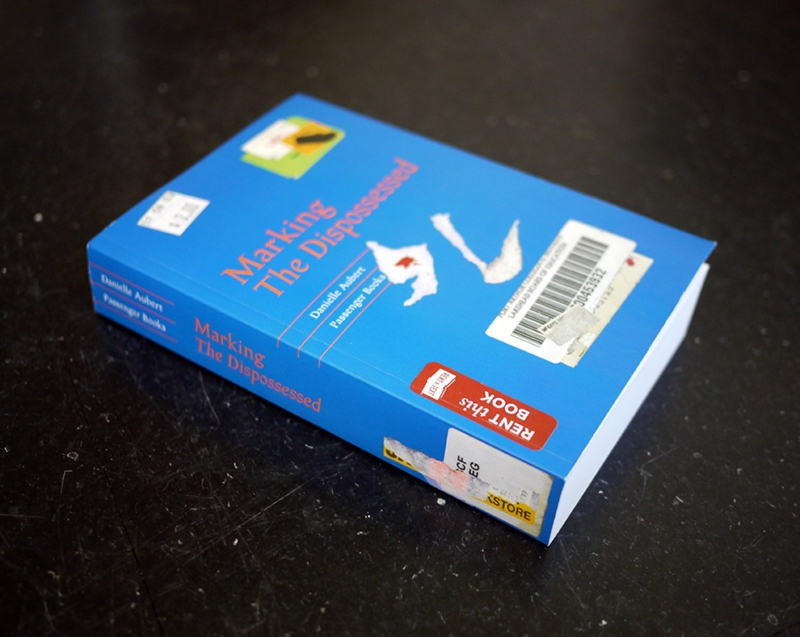

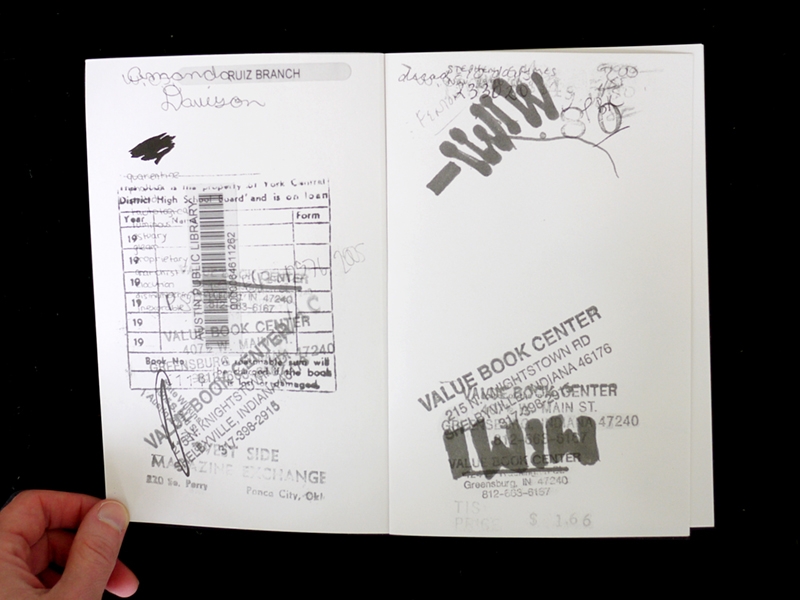

I started buying used copies here and there when I encountered them, I thought there was something tautologically satisfying about collecting dispossessed copies of The Dispossessed. I also liked to see the different covers and the signs of previous ownership — the occasional dog-eared pages, receipts, or bookmarks left inside the pages. I began ordering them online, it was almost too easy to get them, and they were cheap. In less than one hour of searching online I could find five or eight used copies, and they would be shipped to me from around the country. I imagined these copies of The Dispossessed languishing in warehouses with no windows, with bar codes on their spines to make them easier and faster to track and find. They ended up in these warehouses, I imagined, after having been a part of personal collections, where they might have been sitting in someone’s basement. Several of the copies were disaquisitioned from libraries (e.g., New Tecumseth Public Library in Ontario and the Ruiz Branch of the Austin Public Library in Texas).

I had an idea of bringing them together, like farflung brethren. Or maybe a sisterhood of books. That had been dispersed through the world, read (consumed), and discarded. But then I doubted my own impulse to collect, especially a book of anarchist fiction. Many passages in The Dispossessed describes possessions as “excrement”. On Anarres, the accumulation of stuff is a sign of poor health, of badness and grossness. (“They think if people can possess enough things they will be content to live in prison.” p. 138) And here I found myself, confusingly, collecting old copies of this book, which I liked so much, and the more copies I had the more it turned into stuff. Stuff to be moved around my office, stuff to be packed into boxes, or carried here and there. I labeled the books, organized them, looked for patterns, tried to make sense of the various print runs and covers. But now they have become my responsibility, I have all these copies, so many, I go back and forth between feeling like I need to keep them together and feeling like I should distribute them or give them away, but then there will be no more collection.

I looked more carefully at the books with marks, the ones whose readers had taken notes in them, underlined passages, or otherwise left traces of their reading. I don’t often write in books, but The Dispossessed was one that caused me to locate a pen so as to draw a few straight, thin lines in the margin to call attention to certain passages I didn’t ever want to forget. I wanted to take those passages with me (to own them?) and to remember them. (“There was process: process was all.” p. 334) Of course I didn’t remember those passages forever. Also they are not all relevant the way they were at the moment I read them. But still, marking helps to remember, to ingrain. I read a passage, liked it, reached for a pen, went back to re-read and identify which part I really wanted to remember, and marked it. Those steps make the book last longer, make it possible to sit for a little bit with the words. (“No distinction was drawn between art and the crafts; art was not considered as having a place in life, but as being a basic technique of life, like speech.” p. 156)

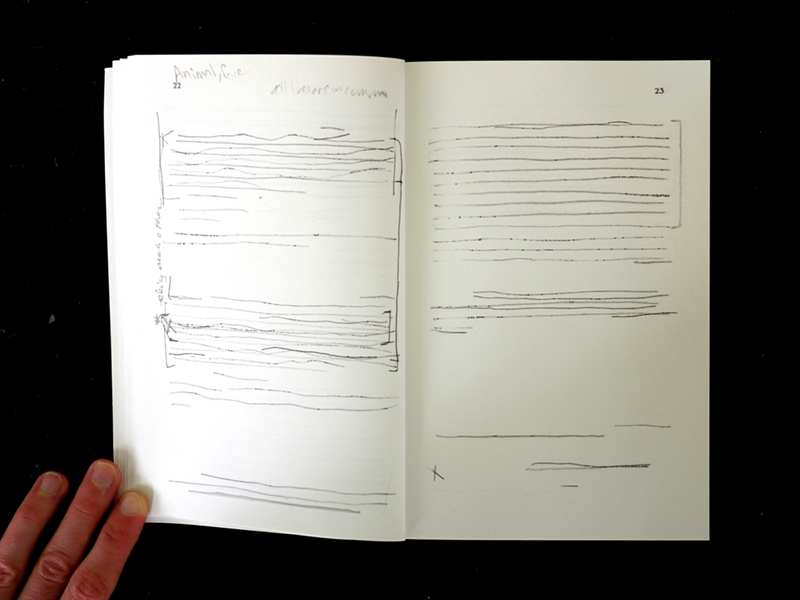

Marking the Dispossessed in a way is made up of marks of possession — it exists around this vexed issue of ownership and past ownership, of use value and uselessness. The more a book is marked, the more value it might have had for the original reader, but the less value it has on the market as a used book (unless the marks are made by a famous person). Of the one hundred used copies I examined, a little over half of them were marked in some way — maybe just by a person’s handwritten name inside the front cover, or stamps from a library. Of those, about half again, roughly 25 books, had handwritten marks left by readers inside the actual text. At first I looked through these to see if there was overlap between these and the marks in my own book, and realized quickly that there wasn’t much. People mark things for different reasons — one was obviously a student in a class, who had been assigned this text and read it attentively, in an academic way, making copious notes and marks and then abruptly stopping about a third of the way into the book. Another person, the owner of book 54, underlined something on almost every single page in the book. At times, this reader underlined every line in a paragraph, individually, in light pencil. They didn’t use the tactic of placing a vertical bar in the margin, as so many other readers did, or bracketing off relevant sections, but preferred to underline. They used a sharp pencil, maybe a mechanical pencil? From start to finish. Another reader, the owner of book 18, seemed to be writing back to the book — not to Le Guin, but to Shevek, the protagonist. “No! No no no! Who is sophomoric enough to think LIFE could or should be painless?” and “I’m going to vomit.” Or “Sounds like me and my friends.” Others make the book easier to reference by noting what is happening on a page (“marriage” “women propertarians” “music”). Several books have just a few words in the entire book underlined ( “perhaps it won’t always be so”).

In this book I collected all the visible marks that I could and layered them page by page. I did not pull underlines or marks from copies of the book that predate the 1991 edition, as those have a different page layout, and the text does not line up as it does in the later editions. In collapsing the marks from each page it is no longer possible to distinguish between individual readers, the marks are made by a group of people-who-have-read-The-Dispossessed. I wanted to see if patterns might emerge (they don’t, really). We can see that some passages get a lot of attention and others don’t, but just as often, a lone reader found something interesting to mark and no one joined them.

The Dispossessed came out in 1974, when the Cold War was still in full effect and the urban uprisings of the late 1960s were a recent memory. But for readers over the last thirty years, different political events would resonate (notes in the margin include “Kent State” “(Beijing) Detroit riots” and “US vs. USSR”). When I sought out other readers of The Dispossessed, I found many who had read it, but they were not in the same space with it as I was — either they had just read finished reading and were still in its immediate afterglow, or it was a distant memory to them. Reading is so intimate, it is just between the reader and the author, and it’s hard to share a reading experience since it really happens inside your head, unless you happen to be reading out loud. We each have our own intense experiences but they are out of sync with others. Something about this particular book made me want to find a collective experience. Alongside this book of marks, I have also been organizing group readings for a used audio book version of The Dispossessed, where people read underlined passages and comments out loud, in unison.

In The Dispossessed, Le Guin enacts a version of anarchism closely related to that of political theorist Peter Kropotkin’s — where people take what they need and are motivated by cooperation rather than competition. Le Guin’s anarchist utopia may be an “ambiguous” one — the story takes place in a society that has already been established for several generations and is a bit frayed. It is nonetheless compelling, especially now, in 2015, as cycles of political upheaval intensify around the world (in Greece, Egypt, Ukraine, Occupy) and so many of us long for viable alternatives to the persistent inequality that results from unbridled capitalism. The most heavily marked passage in the collection of books comes late in the novel. It is spoken by a Urrasti political activist, who explains to Shevek why his very existence is threatening to the political establishment on Urras: “...you are an idea. A dangerous one. The idea of anarchism, made flesh. Walking amongst us.” (p. 295)

I read The Dispossessed almost as a self-help book (let’s start an anarchist society, now!) Anarres, the planet, is a place with a potential for pure togetherness. Does a collection of used books create a kind of togetherness? What kind of intimacy emerges from a group of readers reading out loud together? Or from a set of reader’s marks on the same pages? A secondary text comes out of the collection of handwritten notes in margins, like an echo of the book. I realized that my own reading experience was rather naïve, it was maybe too open, too uncritical, too open and ready to receive. But there is something to knowing my reading was one among many. I hoped to get a sense of a kind of mass readership, to imagine so many individual readers absorbing this text independently, but also together, at different times and in different places.

[Originally written for Marking the Dispossessed, 2015]